Length: 7,500 words.

Reading Time: 25 minutes.

Authors Note: The content has been collected and compiled between May 28, 2012 and February 15, 2020.

This summary of argumentation and debate is organized in the following sections.

- The Benefits of Debate

- The Components of Debate

- The Rules of Debate

- Debate Strategy

- Debate Tactics

- Intellectually Honest Debate Tactics

- Intellectually Dishonest Debate Tactics

- A List of the most frequently used Fallacies

- Tips for Identifying Dishonest Debate Tactics

- The Personal Rewards of Practicing Debate

- Related

Section 8 comprises about 75% of this article.

William F. Buckley and Gore Vidal: The Politics of American Values, 1968.

The Benefits of Debate

Being skilled in debate and argumentation has many benefits.

- It allows one to put forth his own point of view in a reasonable fashion such that others can better understand him.

- It gives listeners the chance to hear conflicting perspectives and decide for themselves what to believe.

- Perhaps most importantly, although most debates attempt to declare one party a winner, there are no real losers in a debate. Even if one cannot attract a popular following to one’s point of view, then at least others will know where he stands and can respect him for his ideas and convictions.

The Components of Debate

Debate has several constituent facets which must be considered, if one is to master the skill.

- The philosophical and logical content of one’s argument must be thoroughly considered, in order to put forth a strong argument that cannot easily be discredited.

- The plan. (See the section on Debate Strategy.)

- The execution. (See the section on Debate Tactics.)

- Psychological concentration and awareness is absolutely necessary to deliver one’s points and to address the viewpoints of the opponent with efficacy.

- A harnessed passion that perseveres is essential in maintaining the focus and energy needed to dominate an argument.

The Rules of Debate

Generally, all formal debates have rules which attempt to keep the debate intellectually honest. Most rules relate to procedures, but rules about procedure can be irrelevant to a personal, live argument or debate. In particular, federal court trials, and their procedures for presenting evidence, have well developed rules.

Roberts Rules of Order, written by Henry Martyn Robert, are used to govern debates in many organizational meetings. For example, one of Robert’s Rules, Number 43 says,

“It is not allowable to arraign the motives of a member, but the nature or consequences of a measure may be condemned in strong terms. It is not the man, but the measure, that is the subject of debate.”

Some debate organizations have rules like The Code of the Debater from the University of Virginia which says, among other things:

“I will research my topic and know what I am talking about.

“I will be honest about my arguments and evidence, and those of others.

“I will be an advocate in life, siding with those in need and willing to speak truth to power.”

But however well one may try to conform to honest debate tactics, there is no guarantee that an opponent might not attempt to use dishonest tactics. Ultimately, the enforcement of these rules depends on the moderator of the debate, and especially upon ones’ own tactical astuteness and the wary anticipation of the opponents’ strategies.

John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon: U.S. Presidential Election, 1960.

Debate Strategy

Each team in a debate could have different strategies, depending on whether they are the government or the opposition.

The government team has one primary strategy: To offer rational support for, and successfully defend, the issue in question.

The opposition team has two primary strategies to choose from: One is to successfully discredit the government’s proposition, and the other is to present an alternative proposition that appears better than the former.

Of note, the opposition team has a slight advantage, in that they are the last to speak, and therefore, they may anticipate the government teams’ strategy and devise an appropriate counterattack.

Each issue could have countless detailed strategies, in terms of how a proposition might be proved either stable or unworthy, and devising this strategy draws heavily upon the creativity and versatility of the team.

Debate Tactics

Debate tactics can be described as being either Intellectually Honest or Intellectually Dishonest. The following two sections will describe each of these tactics in more detail.

Intellectually Honest Debate Tactics

An argument rests upon the strength and validity of its’ logic, so a strong mastery of reason and logic is necessary to be able to be skillful in a debate. Students love learning to recognize fallacies and faulty reasoning. There’s just something empowering about it.

The list of intellectually honest debate tactics is short and easy to remember.

- Revealing errors or omissions in your opponent’s facts.

- Revealing errors or omissions in your opponent’s logic.

All other debate tactics are intellectually dishonest.

Intellectually Dishonest Debate Tactics

Intellectually Dishonest debate tactics are typically employed by dishonest politicians, lawyers of guilty parties, dishonest salespeople, cads, cults, and others who are attempting to perpetrate a fraud. Many businessmen and salesmen, in general, are either charlatans or con men. As such, they have no choice but to employ Intellectually Dishonest tactics both to prove that your opinion is wrong and to persuade you to buy their products and services. Many politicians are also dishonest, seeking to coerce their wills onto the public at large.

Malcolm X and James Baldwin: Black Identity, 1963.

A List of the most frequently used Fallacies

This essay introduces the concept of a fallacy and discusses several common types of fallacies, but it is far from complete. A comprehensive list of recognized fallacies would run into the hundreds, and there is a small industry devoted to identifying and classifying these fallacies of reasoning.

Accusation of being overly “simplistic”: Thomas Sowell identified this Intellectually Dishonest debate tactic on page 80 of his book Intellectuals and Society where he says,

“…certain arguments are unworthy because they are ‘simplistic’ — not as a conclusion from counter-evidence or counter-arguments, but in lieu of counter-evidence or counter-arguments. With one word, it preempts the intellectual high ground without offering anything substantive. Before an answer can be too simple, it must first be wrong. But often the fact that some explanation seems too simple becomes a substitute for showing that it is wrong. Virtually any answer to virtually any question can be made to seem simplistic by expanding the question to unanswerable dimensions and then deriding the now inadequate answer as simplistic”.

Accusation of taking a quote out of context: The debater accuses opponent of taking a quote that makes the debater look bad for being out of context. In fact, all quotes are taken out of context — for two reasons: (1) Quoting the entire context would take too long and federal copyright law allows “fair use” quotes but not reproduction of the entire text. (2) Taking a quote out of context is only wrong when the lack of the context misrepresents the author’s position. The classic example would be the movie review that says,

“This movie is the best best example of a waste of film I have ever seen.”

Which then gets quoted as,

“This movie is the best… I’ve ever seen.”

Any debater who claims a quote misrepresents the author’s position must cite the one or more additional quotes from the same work that supply the missing context and thereby reveal the true meaning of the author, a meaning which is very different from the meaning conveyed by the original quote that they complained about. Furthermore, other unrelated quotes that just prove the speaker is a “nice guy” are irrelevant. The discussion is about the offending quotes, not whether the speaker is a like-able person. The missing context must relate to, and change the meaning of, the statements objected to, not just serve as character witness material about the speaker or writer. Merely pointing out that the quote is not the entire text proves nothing. Indeed, if a search of the rest of the work reveals no additional quotes that show the original quote was misleading, the accusation itself is dishonest. This was done to Mitt Romney in 2012 when he said that, as a consumer, he liked to be able to fire people at service providers so they would be more motivated to do a good job. It was taken out of context as proof he liked to fire people in general when he was a boss.

Ad Hominem: The debater rejects his opponents’ argument on one of the following premises.

- Any claim that the opponent makes is false, because of a particular personal characteristic.

- Any argument that the opponent makes is bad, because of a particular personal characteristic.

The Ad Hominem tactic is a fallacy whenever these implicit premises are false, dubious, or significantly unrelated to the issue of debate.

Note: Ad Hominem tactics are similar to Name Calling.

More: Watch this video about Ad Hominem attacks.

Appeal to a Common Identity: Claiming membership in a group affiliated with audience members. The debater claims to be a member of a group that members of the audience are also members of, like a religion, ethnic group, veterans group, and so forth. The debater’s hope is that, as a result, the audience members will let their guard down with regard to facts and logic, and that they will give their alleged fellow group member the benefit of any doubt or even “my-group-can-do-no-wrong” immunity. This is also called Affinity Fraud.

Appeal to Credentials: Claiming that one’s argument is superior because, “My resume’s bigger than yours!”, which is all the more reason why one ought to be able to cite specific errors or omissions in facts or logic. Yet pride and laziness cause one to appeal to one’s credentials instead.

Note: Appeal to Credentials is somewhat similar to Citing over-valued credentials and Halo effect claims of expertise.

Appeal to Hypocrisy (AKA “tu quo que”): The debater rejects his opponents’ argument by claiming that the opponent’s behavior or beliefs are not consistent with his argument. This tactic is a fallacy unless the topic of debate covers the opponents own lifestyle or professional responsibilities.

More: Watch this video about Appeal to Hypocrisy.

Appeal to Motive: This is a pattern of argument which consists in challenging a thesis by calling into question the motives of its proposer. A common feature of an Appeal to Motive is that only the possibility of a motive (however small) is shown, without showing the motive actually existed or, if the motive did exist, that the motive played a role in forming the argument and its conclusion. Indeed, it is often assumed that the mere possibility of motive is evidence enough.

Questioning the motives of an opponent is not always wrong. It is only invalid when it is used to prove that the opponent’s facts or logic are wrong. If one’s facts or logic are wrong, one’s motive may be the answer why. Questioning your opponents’ motives also makes you look bad, because pointing out a suspicious motive suggests that there is no error, but that you are attempting to insinuate an error by innuendo. A better approach is to simply point out exactly what the error is, and let the facts indicate what the wrong motives might be.

For example, a typical statement used against the marketers of sensationalistic media is to say, “They’re just trying to sell newspapers, books, etc.” It would be more effective to give a few specific examples of how the media’s stories are untrue.

Note: Appeal to Motive is a form of Changing the Subject, and it is a circumstantial case of the Ad Hominem argument.

Appeal to Sunk Cost: Decisions should be based and evaluated on what you know now, where you are now, where you want to go, and what the best way to get there is — only. Taking into account past expenditures of money or effort is flat wrong and utterly irrelevant to decisions. This concept is also embodied in phrases like “water over the dam”, “water under the bridge”, “Don’t cry over spilt milk”, “What’s done is done”, “Throwing good money after bad”, and “Cut your losses”.

Argument from Intimidation: The essential characteristic of the Argument from Intimidation is its appeal to moral self-doubt and its reliance on the fear, guilt or ignorance of the victim. It is used in the form of an ultimatum demanding that the victim renounce a given idea without discussion, under threat of being considered morally unworthy. The pattern is always: “Only those who are evil (dishonest, heartless, insensitive, ignorant, etc.) can hold such an idea”. This is reminiscent of the McCarthy era loyalty oaths, or groups that demand that candidates take a hard line “yes or no” position on complex issues.

Arousing Anger: The debater attempts to get the audience to be angry at his opponent, usually because of his affiliations, a personal quality, or something he said or did in the past.

Arousing Envy: The debater attempts to get the audience to dislike his opponent because the audience is envious of something that can be attributed to the opponent.

Assertion of Non-Existent ‘Rights’: The debater claims that certain conditions or arguments are correct because it, or a supporting fact, is, or should be, a ‘right’. E.g., the ‘right’ to affordable health care and housing, the ‘right’ to a job, a living wage, and so on. An argument based on the Assertion of Rights may be false because such ‘rights’ are based on law jurisdictions or one’s personal sense of justice. In a court of law where the right is proscribed by law, an argument of ‘rights’ may carry merit. Likewise, an Assertion of Rights may be an admissible argument to any audience who agrees. But in the case of arguing the merit of a law itself, arguing on the basis of a ‘right’ loses its Appeal to Authority (which is another fallacy).

For example, “Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” are considered to be inalienable rights in the United States, but elsewhere, it is possible that no such rights exist by law. Furthermore, the subjective interpretation of “Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” is nebulous, subject to personal bias, and has always been open to debate.

In the case of social justice, the assertion of a ‘right’ may be used to argue for various forms of state funded charity contributions, which typically concern the policy of forcing wealthier or less politically powerful Americans to subsidize poorer, or more politically powerful ones. On the other hand, a ‘right’ might be equally offered to justify wealth conservation, privacy, and private ownership. The point is, the justifiability of a ‘right’ is subject to one’s personal and political opinions – which are not necessarily facts.

The one caveat about making an argument through asserting a ‘right’, is that a Right, properly understood, should enable individuals to do what is right and support their ability to do so. In this case, asserting a ‘right’ reverts to a moral argument, and as such, it would be wiser and more intellectually honest to couch the argument within this context.

For an example of this caveat, consider the following argument.

“Access to food, water, shelter, and education are not ‘rights’ guaranteed by law. They are things that humans need to live and thrive. It is morally right for humans to live and thrive, rather than waste away and die. Therefore, these things are necessities, and it is not right that humans should be deprived of these necessities.”

Few listeners would disagree with this argument, even though they might believe that having sufficient material sustenance is not a ‘right’.

Changing the Subject: The debater attempts to redirect the attention of the audience to another subject area, perhaps one in which he can present his argument in a better light. However, he admits to no change of subject and pretends to be refuting the original on-subject statement of his opponent.

Note: This tactic is similar to Red Herring. Citing irrelevant facts or logic is another form of Changing the Subject.

Citing over-valued credentials: The debater accurately claims something about himself or something he wants to prove, but the claim made is one that attempts to get the audience to over-rely on a credential that is or may be over-valued by the audience. For example, some con men point to the registration of a patent, trademark, or corporation as evidence of approval by either the government or the scientific community of the con man’s goods or services.

Similarly, one’s experience or educational level may be cited to establish credence. For example, a person with a Ph.D. in economics may claim that his conclusions on international finance policies are superior to that of a lesser educated opponent. A less knowledgeable person is inclined to agree with him – that is, until another person with a Ph.D. in economics offers another viewpoint to the contrary.

Note: This tactic is somewhat similar to Appeal to credentials and Halo effect claims of expertise.

Claiming privacy with regard to claims about self: The debater makes favorable claims about himself, but when asked for details or proof of the claims, refuses to provide any claiming privacy. True privacy is not mentioning them to begin with. Bragging but refusing to prove is silly on its face and it is a rather self-serving, selective use of the right to privacy. An extreme example might be a U.S. Navy SEAL who claims to be a hero, but who is “not at liberty” to reveal the details because they are military secrets.

Claiming that the opponents’ hyperbole or sarcasm equals dishonesty:

Hyperbole is the use of exaggeration as a rhetorical device or figure of speech. In poetry and oratory, it emphasizes underlying emotions, evokes strong feelings, and creates strong impressions. In rhetoric, it is also sometimes known as auxesis (literally ‘growth’). Hyperbole is also a distinctly American form of humor. The British, in contrast, generally use understatement to achieve humorous effect in similar situations.

Sarcasm is an insincere statement which appears to be appropriate to the situation, but is meant to be taken as meaning the opposite. It usually takes the form of a sharp, bitter, or cutting remark used in a crude and contemptuous manner. Sarcasm is context-dependent and is distinguished by the inflection with which it is spoken. Consequently, the impact of sarcasm is most noticeable in spoken word.

As a figure of speech, hyperbole and sarcasm are used to express emotion and extol the speaker’s charisma, and are usually not meant to be taken literally as facts. In a debate, it is important not to misinterpret hyperbole and sarcasm as facts. Using hyperbole and sarcasm may indeed be rude and insincere, but going one step further to claim that the opponents use of hyperbole or sarcasm is not only rude, but also dishonest, is a logical fallacy. This is because emotionally laden rhetoric expresses the subjective truth of the speaker’s feelings and viewpoints. A more suitable response would be to point out the fact that the speaker is being sarcastic, or else, respond in a similar, sarcastic manner.

Note: Sarcasm should not be used in writing, because the voice inflections and emotional undertones that signify it as sarcasm are not conveyed through writing. As a result, a reader may easily mistake a sarcastic statement to be a sincere one.

Cult of Personality: The debater attempts to make the likability of each debate opponent the focus of the debate on the grounds that he believes he is more likable than the opponent.

False Dilemma: This tactic claims to present “both sides of the story”, however, there may be other perspectives which are not being considered. When this is used in an intellectually-dishonest way it is typically to elevate a bogus argument to be equal to a valid one.

False Premise: The debater makes a statement that assumes some other fact has already been proven when it has not. In court, such a statement will be objected to by opposing counsel on the grounds that it “assumes facts not in evidence”.

Finding Small Error: Citing a slight error or typo as evidence that everything the opponent says is false or that the opponent is “unprofessional” or incompetent (name calling, ill-defined words).

Halo effect claims of expertise: Implying you are an expert in X when your actual expertise is far narrower than X or even unrelated to X. This is the same as saying, “You should know I’m right because I’m really smart.”

The halo effect is the tendency of people who do not know anything about a person, or a professional field, to assume that, “If the speaker is good at A (which would be the first impression on others), then they must be good at everything seemingly related.”

People may falsely believe that a person who has a title or honor, such as a Ph.D., a Rhodes Scholarship, or a Nobel Prize must be an exceeding genius. But in fact, having any title or honor only means that the person in question met the specific qualifications to get that particular award and may or may not have any other qualifications. The same is true of all sorts of mystical accomplishments or experiences like being an Army Ranger, or a Navy SEAL, or a former POW, and so on.

As an example, Dr. Laura arguably did this daily in that she implied she had a doctorate in relationships when, in fact, her Ph.D. was in physiology (the study of the mechanical, physical, and biochemical functions of living organisms). She only has a USC certificate in Marriage, Family, and Child Counseling.

Popular movie stars and singers who only have a high school education, like Arnold Schwarzenegger and Paul Hewson, and who have no training or expertise in government policy, pontificating about government policy are another example of persons using their success in one realm to imply high expertise and wield influence in an unrelated field.

Note: This tactic is somewhat similar to Appeal to credentials and Citing over-valued credentials.

Hearsay: The debater cites something he heard but has not confirmed through his own personal observation or research from reliable sources.

Ill-defined words: In his book Intellectuals and Society, Thomas Sowell says leftist intellectuals use words of approval like,

- complex

- exciting

- fantastic

- innovative

- interesting

- nuanced

and words and phrases of dismissal like,

- simplistic

- outmoded

- reactionary

- turning back the clock

- unworthy

- without basis

These words have little or no meaning therefore cannot convey facts or logic therefore they are intellectually-dishonest debate tactics when used to argue a point.

See also: Filtered Reality, Verbal Virtuosity, and Wine Taster Approval.

Innuendo: An indirect remark, gesture, or reference, usually implying something derogatory.

Insinuation: A sly, subtle, and usually derogatory reference which is used to cause the audience to associate the opponents’ arguments with an unfavorable impression.

Mockery: 1. Derision; ridicule. 2. An absurd misrepresentation or imitation of something. The problem with mockery is that it discredits the opponent without offering any facts or logic.

Motivation of the end justifies dishonest means: The debater admits he is lying or using fallacious logic but excuses this on the grounds that he is motivating the audience to accomplish a good thing and that the end justifies the intellectually-dishonest means.

Name Calling: The debater tries to diminish the argument of his opponent by calling the opponent a name that is subjective, unattractive, and often profane. For example, cult members and bad real estate gurus typically warn the targets of their frauds that “dream stealers” will try to tell them the cult or guru is giving them bad advice. Name calling is only intellectually dishonest when the name in question is ill defined or is so subjective that it tells the listener more about the speaker than the person being spoken about. There is nothing wrong with using a name that is relevant and objectively defined.

The most common example of name calling is in using the adjectives “negative” or “bitter”.

For example, college professors often criticize athletic coaches as being “negative” or “too intense”. Meanwhile, the word “professor” is used sarcastically as a name-calling tactic by the coaches who are the targets of the criticism in question. The truth is that professors specialize in disciplining the mind, while coaches specialize in disciplining the body. Both are necessary to produce successful youth.

Another example is how former employees accuse their boss of being shifty, stingy, or dishonest. Meanwhile, these same people are dishonestly dismissed by their former employer as being “disgruntled” or “bitter”. The truth is that neither one fulfilled the expectations of the other, neither could they agree on how to complete the tasks at hand.

These are all efforts to compel the audience to agree with the speaker and take his side. It is dishonest because (1) it changes the subject, (2) it relies heavily on emotions and opinion, and (3) the speaker cannot refute the facts or logic of the opponent.

Note: This tactic is similar to Ad Hominem.

Negative Pregnant: Many intellectually dishonest debate tactics are variations of Negative Pregnants. A negative pregnant is a statement that seems to deny something but when closely examined only denies a narrower question that was not asked. The classic example would be the question, “Did you murder Jones?”, followed by the answer, “I did not shoot Jones”. Although the answer is phrased in the negative — “I did not…” — it contains, or is “pregnant” with the opposite implication: “Yes, I killed him but I didn’t do it with a gun.” In most cases, the person responding is trying to seem like they are saying no when in fact they are not saying no to the actual question that was asked, meaning they must be saying yes. They are changing the subject of the question by answering a question that was not asked. The answer offered does not make them look as bad as would the answer to the actual question that was asked.

Roughly speaking, you could reasonably reply to all negative pregnant answers by saying, “So you admit, you really agree with me. But you’re trying to hide that fact by dishonestly appearing to disagree with me (by avoiding a direct answer to my question)?” During the Watergate scandal, this was called a “non-denial denial.”

Peer approval of subjective opinion: A logical fallacy may be lurking whenever a subjective statement is “proved” to be correct by citing the approval of political allies in the same subject.

Peer approval has value when it relates to objective standards like those in mathematics, chemistry, and physics. In academic circles, this is called “peer review”. Such peers check the accuracy of calculations, the cleanliness of laboratories, and whether they can replicate the results in their own experiments. But peer review is of little probative (proving) value when it relates to highly subjective fields like sociology, economics, or women’s studies. Peer approval is especially misleading when the peers in question, and indeed the whole field or large portions of it, have a particular political agenda.

The weakness of peer review is when it is preemptively considered correct by the peers selected for the review, or those who have a confirmation-bias.

In The Law of Group Polarization, Cass R. Sunstein argued that groups of like-minded people in deliberative environments tend become more radical in their ideas. For instance, a group of professors in favor of affirmative action coming together to discuss how to defend affirmative action will likely become more radically in favor of affirmative action as a result of the interaction.

Bernard Manin warned of the dangers of democratic, deliberative forums, in that supporting arguments are presented, while sensitive information is suppressed. This leads to people on all sides to form echo chambers where their ideas are bounced around, developed, and yet go unchallenged. He expressed the importance of public debate to clearly identify the issues at stake.

Playing on widely held fantasies: The debater offers facts or logic that support the fantasies of the audience thereby triggering powerful desires to believe that override normal desire for truth or logic.

Political Correctness: This is not exactly a debate tactic because it is more accurately described as a refusal to debate. Those who insist on being “politically correct” have a list of statements that, to them, cannot be debated. If you say anything that conflicts with the list, the Politically Correct rules are used to denounce your ideas (and you as a person, which is a form of Ad Hominem) in the most extreme ways, commonly alleging racism, misogyny, idiocy, “hate speech”, etc. Although Political Correctness claims to be against discrimination, the realm of the Politically Correct is a zone that discriminates facts and logic. Thus, people who prefer to depend on Political Correctness to win their arguments are bigoted and lazy, because it’s easier to be certain when you only have to check a list than when you have to figure stuff out using facts and logic.

Protest-too-much quantity of sources: This is citing an overly long list of legal or other purportedly-authoritative citations to prove the opponent is wrong. Part of the trick of this debate tactic is to confuse the opponent, or to get him to spend days researching all the citations.

For example, Actor Wesley Snipes went to prison after failing to pay his income taxes on the grounds that they were unconstitutional. People who claim income taxes are unconstitutional typically cite a book-length list of court decisions and statute sections to “prove” they are right. In fact, income taxes are constitutional because of the XVI Amendment to the Constitution. This decision was upheld by numerous court cases over the past century, which have dismissed the long lists of legal citations as “frivolous,” and have typically fined the litigant for pursuing the suit at all.

Red Herring: The debater introduces an irrelevant, but very interesting topic, with the intention of drawing attention away from the opponents’ original argument.

Note: This tactic is similar to Changing the Subject.

More: Watch this video on the Red Herring trick.

Redefining Words: The debater uses a word that helps him, but that does not apply, by redefining it to suit his purposes. The assumed truth of the revised definition may appeal to intuition, and may not be explicitly given. For example, leftists calling government spending “investment”.

Rejecting facts or logic as opinion: It is true that everyone is entitled to their own opinion. But everyone is not entitled to their own facts or logic. Nor is anyone allowed to characterize a factual/logical argument as merely the opinion of the opponent. Facts are facts. 2 + 2 = 4 is not my opinion. It is a fact. If you explain your conclusions with facts and logic, and your debate opponent dismisses those facts and logic as merely “your opinion”, then that is a dishonest tactic.

Resorting to a Pedantic Argument: Pedantic means to overrate the importance of minor or trivial points of an issue, while neglecting the weightier matters. The strength of a pedantic argument is that it might be used to distract and confuse one’s opponent, similar to citing irrelevant facts or logic. The weakness of a pedantic argument is that it displays a lack of scholarly judgment or sense of proportion.

For example, it is pedantic to insist that all characterizations of large data sets must be stated in percentages to the third or fourth decimal point. Of course, adding exact decimal figures does not change the order of magnitude. Also, such data is not available in most cases and would take considerable effort to dig up if it did exist. Hyperbole exists to deal with such situations.

Rotten Solution: Presenting a real, working solution to the proposition with consequences that are so onerous that the entire proposition is then rendered unstomachable. Often times, but not always, the intent is to embarrass the opponent, or belittle his argument so much that it becomes a joke.

For example, if the proposition concerns the affordability versus the benefits of social security and medicare, then a Rotten Solution would be to enact voluntary euthanasia for anyone above the age of 65.

The strength of the Rotten Solution is that it distracts the audience from a serious consideration of the original argument. The weakness is that using this technique may alienate the audience if they have a large emotional investment in examining the original argument.

Note: The Rotten Solution is a variation of Trolling.

Sarcasm: Sarcasm is a statement which is the opposite of what you believe. The key in expressing sarcasm is to say it in a tone of voice that reveals how ridiculous you think the statement is. The phrase, “Yeah, right!” is the classic example.

Repeating sarcasm without indicating it was sarcasm is a dishonest tactic.

One of the cardinal rules when you give an unvideoed deposition is to never use sarcasm. For example, dishonest trial lawyers will quote what you said in the deposition transcript and leave out the sarcastic tone of voice. For example, a lawyer asks if you believe the sun rises in the west and you say, sarcastically, “Yeah, right.” Then in court, he reads that part of the definition making it sound like you agreed with the statement that the sun rises in the west.

Scapegoating: The debater blames problems on a person or group (other than the audience).

Note: This is a negative version of Playing on widely held fantasies, in that it plays on widely-held animosities, dislikes, or stereotypes.

Slippery Slope: Assumes a chain of inferences with likely outcomes, and claims that if the last inference is unwanted, then the first inference should be avoided. This is a logically weak tactic because the probability is compounded with each additional inference.

An example of the Slippery Slope goes like this.

“If you don’t study hard, then you won’t pass the test. If you don’t pass the test, then you’ll fail the class. If you fail the class, then your GPA will go down. If your GPA is too low, then you can’t get into a good college. If you don’t go to a good college, then you won’t find a good job. If you don’t get a good job, then you’ll be poor. If you’re poor, then you’ll have to work 10 hours a day. If you work too much, then you’ll have no time for family. Eventually, your wife will leave you for a wealthier man. So if you want an easy life and a good marriage, then you’ll have to stay up late to study tonight.”

Although there might be some intuitive truth to this, it is by no means a certainty. Therefore, it is a weak argument.

More: Watch this video on the Slippery Slope fallacy.

Sloganeering: The debater uses a slogan rather than using facts or logic. Slogans are vague sentences or phrases that derive their power from rhetorical devices like alliteration, repetition, cadence, or rhyming. Some slogans also appeal to human mythos and desire for inspiration. Examples of this technique include these.

- In sports, coaches frequently rely on clichés, a less rhetorical form of slogan, to deflect criticism.

- Rich Dad Poor Dad’s “Don’t work for money, make money work for you!” is a classic example.

- The U.S. military once had the slogan, “Be all that you can be… in the Army!” This is a woefully inaccurate portrayal of military duty, especially when considering that some enlisted service men perish in the course of duty.

Stereotyping: The debater “proves” his point about a particular person by citing a stereotype that supposedly applies to either (1) the subject of the argument, or (2) the group that the opponent is a member of.

For example, Professor David Romer of California Tech did a study that found American football coaches should go for a first down far more often and kick far less on the fourth down; Some coaches laughed and rejected his findings because “he is a professor”, turning the report sideways when reading it, and dismissed Romer as an “Ivory Tower intellectual” who is too far removed from the game to have any authority in the matter. If Romer is wrong, it is because of an error or omission in his facts or logic; not because he is a college professor.

Straw Man: The debater introduces a distorted, exaggerated or otherwise misrepresented version of the opponents’ argument, criticizes it, and then claims to have refuted the original argument. This tactic involves a knowing or willful deception and a refusal to commit to logical coherency in the debate. It also causes the audience to conclude that you are either (1) intellectually dishonest, or (2) woefully uninformed about the true nature of your opponent’s arguments.

More: Watch this video about the Straw Man fallacy.

Theatrical fake laughter or sighs: This can be wordless, but it says, “What you just said is so ridiculously wrong that we must laugh at it.” It is intellectually dishonest because it is devoid of any intelligence, facts, or logic.

Examples of this tactic include the following.

- Al Gore made the *sigh* debate tactic famous in the 2000 presidential debates and the ensuing Saturday Night Live parodies of it.

- The whole Democrat party laughed at Sarah Palin during the 2008 U.S. presidential election primaries. They were successful with this tactic, in spite of the conspicuous absence of any evidence or logic that could explain why she was made into a laughingstock.

- Hillary Clinton tried theatrical laughter without much success in the 2008 presidential campaign.

- On June 2, 2009, Dilbert cartoonist Scott Adams celebrated this tactic in a comic strip that had Dilbert saying to the pointy-haired boss, “I like what you’ve done with your dismissive scoffing sound.”

- In 2010, Nancy Pelosi used a verbal version of this when she said, “Are you serious? Are you serious?” in “response” to the question, “Where in the Constitution is the federal government authorized to order Americans to buy health insurance?”

Hillary Clinton and Donald J. Trump: U.S. Presidential Election, 2016.

Tone Policing: An approach which derails a discussion by critiquing the emotional undertones of the message, rather than the message itself. Tone Policing is not easily detected in formalized debate because a structured debate strategy requires people to distance themselves from their own emotions of anger, frustration, or fear, in order to remain logical and reasonable. But sometimes these emotions are a central part of the issue, and should not be neglected.

The strengths of Tone Policing include the following.

- Because Tone Policing suggests that people should distance themselves from their own emotions of anger, frustration, or fear, in order to be taken seriously, it is a useful tool to deal with firebrands who are superficially dramatic and emotionally domineering.

- Tone Policing can be beneficial to debate when it is used to control emotional distractions, such as boisterous interruptions and heated objections to the speaker’s arguments.

The weaknesses of Tone Policing include the following.

- It assumes a manufactured binary condition, that emotion and reason cannot coexist, and that reasonable discussions should not involve emotions.

- It assumes that the outcome of the discussion will be one of mutual agreement, which may or may not be an acceptable outcome.

Tone Policing is dishonest when the following characteristics are present.

- It assumes that emotional expression curbs the logical process and hampers finding a solution.

- It forbids an authentic, emotional expression of communication, which is often necessary to establish a meaningful identification with the audience.

- It exercises control over a conversation by shaming or dismissing any emotions involved with the issue.

- It is used to denigrate or dismiss the content of an argument as being disrespectful or uncivil.

- It is used to avoid difficult or uncomfortable topics.

- It is used as a subtle silencing tactic.

Trolling: The practice of combing through the opponents’ arguments and emphasizing an inflammatory, extraneous interpretation of their argument. The intent is to aggravate or exasperate the opponent so much that they are provoked into an emotional response and thereby abandon their faculties of reason. Trolling is done either to fatigue or frustrate the opponent, or to elicit a dramatic response for the Trolling person’s own amusement.

Trolling is dishonest because the Trolling person insists on propagating his own prejudiced bias, and does not enter into the debate in good faith. The resulting acrimony is therefore disruptive to the logical process. Furthermore, Trolling rarely contributes any meaningful content to the discussion.

More: Read this essay on Trolling.

Unqualified Expert Opinion: The debater gives or cites what is purported to be an expert opinion which is not actually from a qualified expert. In court, an expert must prove his qualifications and be certified by the judge before he can give an opinion.

Vagueness: The debater uses language that seems to cite facts or logic, but his terms are so vague that no facts or logic are present. Some examples of Vagueness would be statements like these.

- It is well known that happiness is important to success and well-being.

- The North and South fought the Civil War for many reasons, some of which were the same and some different.

- Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

Neils Bohr and Albert Einstein: The Nature of General Relativity, 1927.

Tips for Identifying Dishonest Tactics

Intellectual dishonesty is difficult to identify in real time, especially for the young or uninitiated. It takes a few years of study and practice, as well as a well-honed skill set (and perhaps some natural ability), for one to become adept at discerning Intellectual Dishonesty in real time.

Although it is important to develop your skill in an Intellectually Honest debate, you should be aware that about 90% to 95% of the statements made by your opponents will be Intellectually Dishonest, and will be used powerfully to prove that you are wrong. It will help you to sort out the truth of a matter if you are well acquainted with how almost all arguments consist of one Intellectually Dishonest debate tactic after another.

As such, it may be helpful to focus on how any given fallacy can be understood using the basic concept of argument analysis. As such, these fallacies may be classified as one of the following.

- Fallacies of logic are when the relationships between the causal factors and their resultant conclusions are assessed incorrectly or unfairly. This would include “logical leaps of faith”.

- Fallacies that arise from false, questionable or implausible premises, including distorted or exaggerated facts and circumstantial evidence. Of note, statistics and data analyses can be skewed or shrewdly selected to indicate almost any viewpoint desired.

- Fallacies of content occur when the subject presented does not address the issue at hand, e.g., Ad Hominem (either directly abusive or guilt by association), Appeal to Hypocrisy (tu quo que), Appeal to Popular Belief (or practice), Appeal to Authority, False Dilemma, Slippery Slope, etc.

- Fallacies that Violate the Rules of Rational Argumentation, e.g., Straw Man, Red Herring, Begging the Question (in either the broad or narrow sense), etc.

Here’s some advice based on the book by Carl Sagan, The Demon Haunted World.

These are warning signs for deception! The following are suggested as tools for testing arguments and detecting fallacious or fraudulent arguments:

- Wherever possible there must be an independent confirmation of the facts.

- Encourage substantive debate on the evidence by including knowledgeable proponents of all points of view.

- Arguments from authority carry little weight (in science there are no “authorities”).

- Spin more than one hypothesis. Don’t simply run with your first idea.

- Try not to get overly attached to a hypothesis just because it’s yours.

- Develop your own cognitive processes for reviewing the arguments of others and deciding what to believe.

- Continue to review and memorize all these tactics and techniques.

More: Watch these videos to learn more about identifying honest and dishonest arguments.

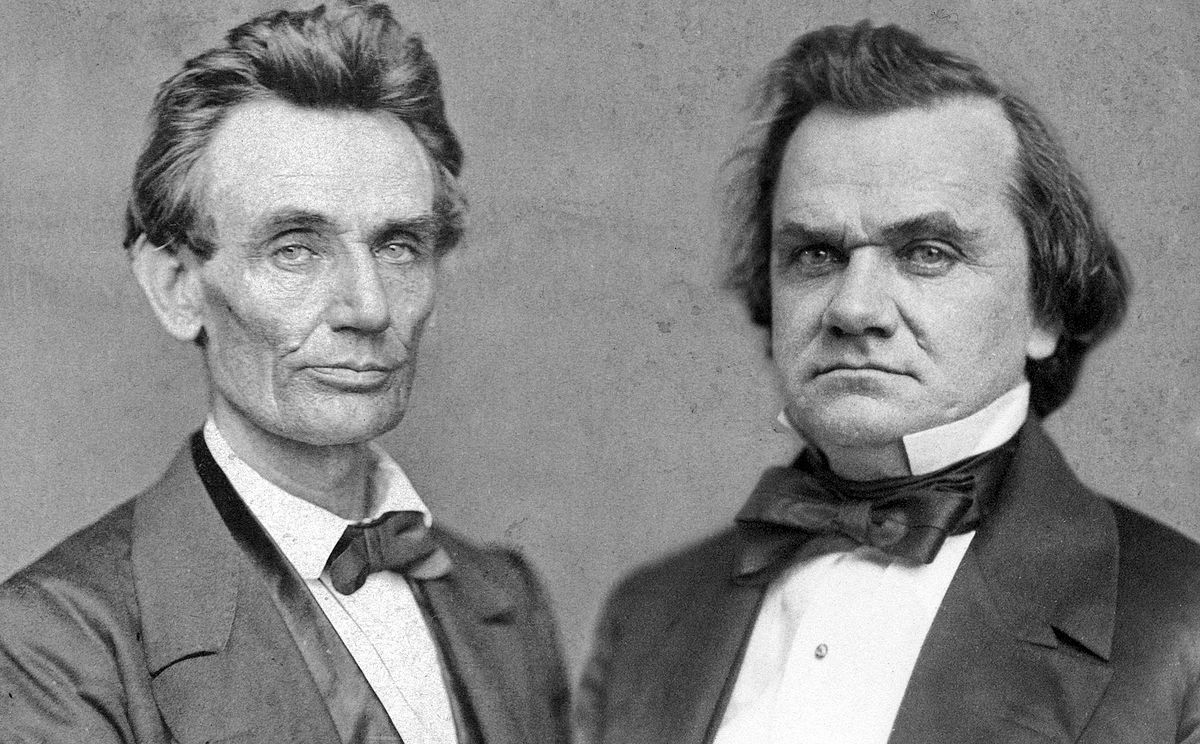

Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas: Illinois Senatorial Election, 1858.

The Personal Rewards of Practicing Debate

Learning debate tactics has the potential to change your life. Do not be surprised if you find yourself becoming more confident in verbal altercations. You may find yourself returning to study these more and more over time.

One of the great disappointments of life is discovering how thoroughly dishonest most people are. Some people will, on the slightest provocation, fire off a statement or paragraph that contains three, four, five, or six different intellectually-dishonest arguments in a matter of seconds. People like this don’t even need to study or practice debate, because, unfortunately, being dishonest seems to be an innate part of human nature. Instead, it takes study and practice to revoke one’s own natural inclination to resort to dishonest debate tactics. The rewards for doing so include the following, and perhaps others.

- The ability to understand how the viewpoints of others are different from your own.

- The ability to weigh the value and impact of information.

- The ability to use knowledge and reason to make better decisions.

- An increased ability to discern lies and falsehoods.

- Personal enhancement of one’s own character and charisma.

- The ability to convince others of your way of thinking.

- Enhanced self-assurance.

- Increased self-confidence.

Best wishes~!

Related

The following sites contain descriptions of many other intellectually dishonest debate tactics.

- Don Lindsay: A List of Fallacious Arguments

- Glen Whitman: Logical Fallacies and the Art of Debate

- Wikipedia: List of Fallacies

Pingback: New Page: Argumentation and Debate | Σ Frame

Good stuff. I’m not at all into debate, but I can see the importance of it for some pursuits.

LikeLike

Pingback: How to countermand the intellectual dishonesty of a Karen | Σ Frame

Pingback: The Shepherd and the Crook | Σ Frame

Pingback: Let the kids eat cake to keep them out of trouble! | Σ Frame

Pingback: 2020 Sigma Frame Performance Report | Σ Frame

Pingback: 8 Things that Increase Discernment | Σ Frame

Pingback: The Male Hamster InAction! | Σ Frame

Pingback: Glorifying God in the Flesh | Σ Frame

Pingback: Where Shame Tactics become Witchcraft | Σ Frame